In the years immediately preceding World War I, as the U.S. was abandoning its neutrality and beginning to intervene on the side of the Allies, there was a wave of anti-German sentiment and personal violence both nationally and in Iowa.

Communities and regions such as Calumet and Liberty Township, which were home to many recent German immigrants, had already experienced inter-ethnic friction even upon the Germans’ arrival to the region beginning in the 1880s. In the decade following the 1909 Calumet German Band photo, however, the patriotic fervor caused by WWI exacerbated the existing anti-German sentiment and brought strong nativist feelings and expressions to a head.

The U.S. entered the war with a congressional declaration on 6 April 1917, and in November, Iowa Governor William Lloyd Harding(1) (1877-1934) created the Iowa State Council for Defense to promote Americanism and patriotic loyalty (and additionally to serve his political purposes). Similar “defense councils” were implemented in every state, in support of a statement by President Woodrow Wilson in his Declaration to Congress on 2 April 1917 that “millions of men and women of German birth and native sympathy live amongst us…. [I]f there should be disloyalty, it will be dealt with with a firm hand of stern repression.”(2)

The president called, and the defense councils answered. In Iowa, the Iowa State Council for Defense advised Gov. Harding that the teaching of German in public schools should be banned, and the reported burning of German books reinforced that point. Council chairperson Lafayette Young, a newspaper editor and publisher, even stated that “disloyal” persons within the state should be impoverished and imprisoned.

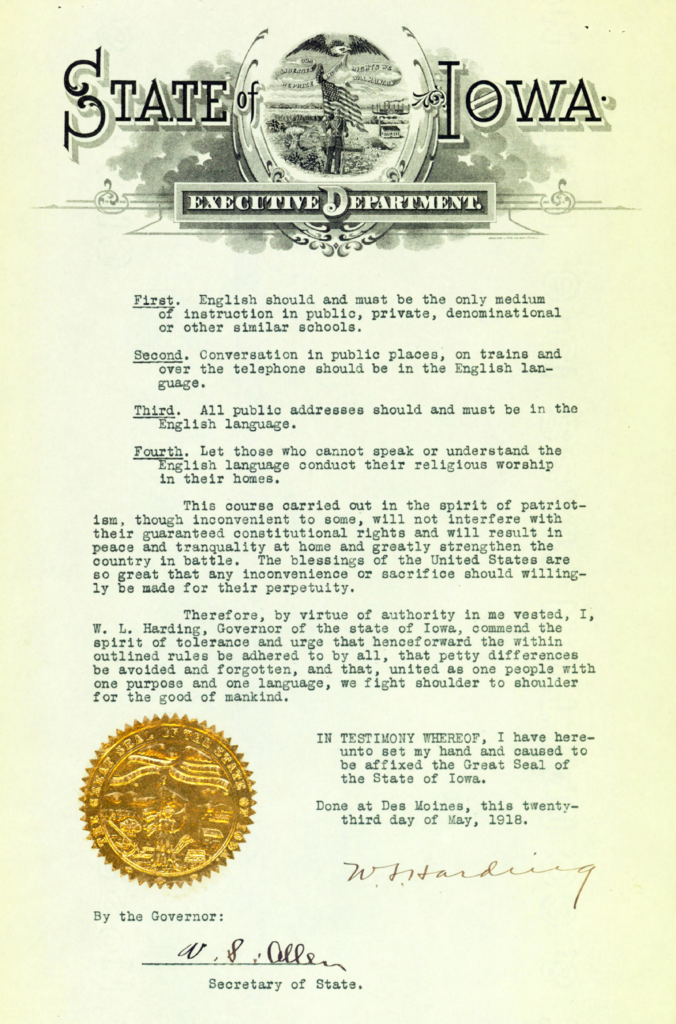

The “Babel Proclamation”

On 23 May 1918, Gov. Harding issued what came to be known as the “Babel Proclamation,” which forbade the speaking of any language in public other than English. (In Harding’s proclamation he somehow also managed to state, “I … commend the spirit of tolerance.”) Violators of the “Babel Proclamation” were issued fines; most such violators were caught when local telephone operators listened in on phone conversations. Although the proclamation caused an outcry both within the state and elsewhere, it was officially repealed only after the end of the war, on 4 December 1918.

In O’Brien County, the “Babel Proclamation” led to open animosity between neighboring towns; some, such as Calumet, had a large proportion of German-Americans, and others, such as nearby Sutherland, had a somewhat smaller proportion. But even within the towns themselves there was discord, as neighbors clashed with neighbors over the expression of German culture and especially the speaking of the German language.

In the run-up to the war, Calumet, Sutherland, Primghar, Sheldon, and other towns had established their own semi-official “Home Defense Leagues,” which anticipated the state leagues that would follow President Wilson’s address to Congress, as patriotic expressions of support for U.S. war involvement. By the time of the U.S. war entry, such leagues were already taking action against German-Americans in their midst, irrespective of whatever other beneficial effect they might have had in projecting a unified front for the Allies.

In early 1918, the town of Sutherland adopted an official policy against the speaking of German, and it posted public placards to this effect. Shortly thereafter, on 13 March 1918, Fred Nott, a member of the Calumet Home Defense League and a Justice of the Peace, wrote to the governor to point out that the league was posting similar warning placards within Calumet. (Note that in this excerpt and those below, the quotations reproduce misspellings and other errors from the original.)

Now, the League at Sutherland prohibites the speaking of the German and Austrian languages in public and our League is having signs printed and intends to post same asking the people to refrain from speaking the German and Austrian language in public places, also over the telephone.

Now these leagues do not intend to work hardships on old people who vannot talk the Elglish language, but do insist that people who can talk the English, talk it in preference to the German, and some people who oppose these movements delcare they will boycott the members of these leagues and the town wherein these signs, prohibiting the German and Austrian, are posted.

Now are you with us in our actions and what pressure can we bring to bear on boycotters.(3)

Steps such as those taken in Sutherland and Calumet, as well as political pressure on the governor through letters such as Nott’s, seemed to mutually reinforce each other and to whip up support for further action. Once Harding issued the “Babel Proclamation,” local defense leagues assiduously supported the governor’s directive and often overstepped the bounds of decorum or even civility. Mayors, business leaders, and self-appointed guardians took actions to police the speaking of anything other than English in public and sometimes even in private settings.

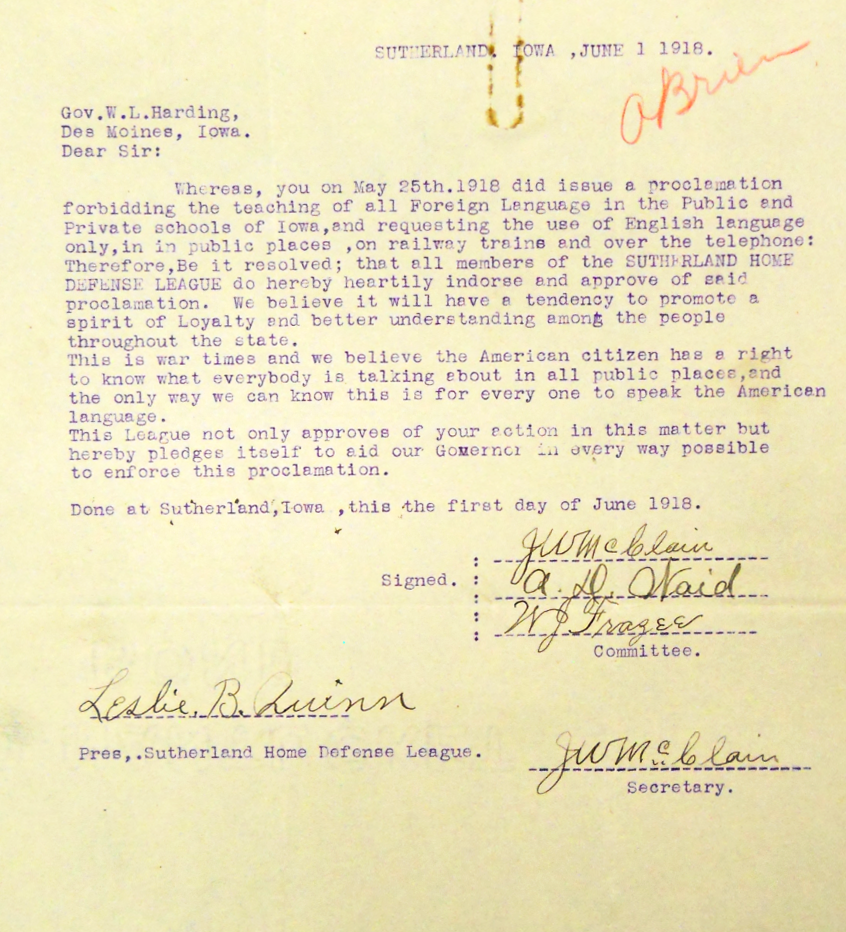

The Sutherland Home Defense League quickly passed a resolution — “This is war times…” the league argued — on 1 June 1918 in support of the governor’s proclamation, and the town of Hartley passed a similar resolution on 30 September 1918.

Trouble in the Township

Calumet resident and leader Fred Nott, who seemed to be particularly zealous in his role, wrote to the governor again on 1 June 1918, apprising him of local violations and asking for the governor’s assistance:

What advice can you give me on how to handle violaters of your language Proclamation. We have some people here that violate same especially over the telephone and I thought perhaps with my authority as Justice of the Peace — a peace officer — could handle those cases as State cases — give the parties a small fine, fine made payable to some army cause, and let them go, but I want your opinion on same or such other advice as your might tender.(4)

On 29 November 1918, Nott followed up with another letter to the governor, revealing that not only were the Calumet Home Defense League’s efforts facing resistance but that the league and the mayor were not exactly on the same page:

Some of the Germans in this town came to me today asked if they could talk the german language now — they seem to think your proclamation is off now and some make it their boast they will talk all the German they want too. Would like your opinion on what to tell them.

The fact is they are talking German here by the wholesale — you would think it was Berlin instead of Iowa and the Mayor of the Town was asked today where the signs were prohibiting the speaking of the German language, which were put up by our Defense League, and replied “I do not [know] what become of them and do not know as it is any of your business.”(5)

Trouble in the County

Officeholders and citizen activists in other O’Brien County towns were equally active in their vigilance.

Primghar

C. Williams wrote to the governor on 28 May 1918, saying, “we have a number here who [are] American born who can talk the American language but insist on talking German which seems to be done for general meanness, in spite to us Americans.”(6)

Paullina

Mayor H. G. Culp wrote to the governor on 3 August 1918, apprising him of the fact that “We have a few people in our town that insist on talking the German language on our streets,” and offering a suggestion: “I presume the best thing would be to send a Secret Service man here.”(7)

Sheldon

Lewis Eichman wrote to the governor to ask what he could do as “chirman” of his rural telephone line to enforce compliance. Eichman’s letter was on 6 January 1919, long after the end of the war and after the repeal of the proclamation:

some say thay dont have to use the English Language and some say thay wont use the English Language and some say that no body can make them use the English Language what about your state law I have don my best and all I can do all the people on this telephone line can talk English we are going to have our yearly meeting soon what can you do to help me with this I am the chirman of this line at present so help me if you can and answer this letter at once(8)

Trouble in the Social Centers

Some informers were certain that someone, somewhere, was not speaking English, even if the informer could not gain access to the private venue where this infraction was alleged to be taking place. On 5 June 1918, Sheldon resident W. H. Brance wrote to Gov. Harding, reporting about hearsay violations (“it is said that”) but suggesting that greater specificity in the governor’s “law” (it was not a law) would solve the problem:

Esteemed Sir: — We are experiencing considerable difficulty in having our Holland and German older people talk English on the streets of Sheldon. The Hollanders here have a Hall, where none but Hollanders are allowed, and it is said that they talk Holland conversation as much as they choose. If you would insert the word must instead of should in rules two and three, and attach a penalty for violating these rules, and state exactly what it would be, it would enable the Mayor, the Marshal and his assistants to enforce the law.(9)

Trouble in the Church Pews

For some, the “Babel Proclamation” led to confusion about the extent of its strictures. F. W. Horton, a physician in Sanborn, wrote to the governor on 17 August 1918, stating that “We have two Holland churches here” and reporting that in one church the “minister uses the Holland language in part of his service”; Horton asked whether the governor had given his permission for an exemption.(10)

A. H. Semmann, pastor of the Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church in Paullina, wrote to the governor on 30 July 1918, apparently without sarcasm, asking for clarification even about congregational singing:

Honorable Sir: —

Please pardon my intrusion into your precious time for just a moment.

A little difference of opinion has arisen regarding the language to be used in singing of hymns in church-services. We are living up to the letter of your proclamation and its explanation regarding the sermons in English and foreign languages, but the question is not clear to some whether or not it is permissible to permit the congregation, especially those members, who are not well able to read the English language, to sing hymns in a foreign language.

I would greatly appreciate an early reply from you, since this would help much to gring about a more uniform practice.(11)

Similarly, Herman J. Brackney, a Sheldon surgeon, wrote to the governor on 6 July 1918 to report on a controversy within Primghar’s Defense Council. According to Brackney, “Holland Churches” were causing havoc because “several preachers cannot talk English.”(12) Primghar’s Defense Council would allow no loopholes, but Brackney and other letter writers reported in alarm that pastors in neighboring Sioux County were being allowed a “50/50” exemption to conduct part of their service in English and part in Dutch. H. L. Avery, chairman of the O’Brien County Council of Defense, asked, “how can they use any thing but the English language.”(13) Brackney reported a concern that O’Brien County congregants might flee to the more forgiving Sioux County’s “50/50” churches in “Boyden, Hospers, and Matlock” to find more hospitable religious services.(12)

Trouble in the Pool Halls

Members of the Calumet German Band were not immune from the controversy. On 20 June 1918, J. W. McClain, the secretary of the Sutherland Home Defense League, reported to the governor that Henry Friedrichsen was a violator, along with his brother John, and that their own brother Herman would be willing to testify against them. The infraction had taken place in the Calumet pool hall.

Dear Sir:

Received your instructions this morning in regard to reporting violations of your Language proclamation.

Beg to report that John Fredricksen and Henry Fredricksen were heard talking German in the Pool Hall at Calumet few days ago. We have two witnesses that will testify to this (Bert Worden and Herman Fredricksen). The defendants receive their mail from Sutherland but live near Calumet.

Please attend to these fellows at your earliest convenience,

And oblige,

J. W. McClain, Sec. Sutherland Home Defense League.(14)

Trouble Right Here in Calumet City

Calumet resident Mrs. S. W. (Mary McCulla) Woodworth reported to the governor on 22 Dec 1918 — after the war’s end —that she was “ready to testify” that German had been detected in telephone conversations and that even the Calumet postmaster had been heard speaking German:

Am writing to inform you that there is a great deal of German talk in this community. Particular cases that I have heard and am ready to testify to have been over the telephone. For a time this summer and fall they were scared and didn’t talk German but since the armistice was signed they have become as bold as before the war, will get possession of the phone and we Americans can simply wait their pleasure. A friend of mine in town told me that she heard the post master talking German in the post office a few days ago.

I heard your address at the Sutherland Fair last fall and hope that you will attend to this matter as you said then. I have several relatives “over there,” one a brother, and feel pretty strongly on this subject. Calumet has been a hot bed of pro-Germanism all during the war and it hasn’t been any easy matter to live near it.(15)

Legacy

The “Babel Proclamation” was unique in form, but unfortunately it is not the only example of reactionary politics aimed to exploit and inflame latent nativism and intolerance. Nevertheless, it seems to represent a culmination in this particular wartime era in its anti-German sentiment. In the history of the U.S., a nation founded by immigrants, Gov. William L. Harding remains the only governor — to date — to have taken an executive action to outlaw the public speaking of a language other than English.

< return to “The Cultural Milieu” section

Footnotes

(1) William L. Harding’s tenure as the 22nd governor of Iowa encompassed the years of World War I; he served two two-year terms, from 1917 to 1921. Harding had been born in Sibley, Iowa (Osceola County), coincidentally just 40 miles from Calumet. Harding studied at Morningside College in Sioux City and received his law degree from the University of South Dakota. Prior to his gubernatorial election, he served for six years as a Republican member of the Iowa House of Representatives, then as lieutenant governor from 1913 to 1917. His term of office as governor was characterized by scandal in addition to his notable hostility toward immigrants; after he was found to have accepted a bribe to pardon a convicted rapist, Harding was censured by the legislature. Perhaps wisely, he did not run in 1920 for a third term.

(2) President Wilson’s Declaration of War Message to Congress, April 2, 1917; Records of the United States Senate; Record Group 46; National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/address-to-congress-declaration-of-war-against-germany.

(3) “Language and Home Defense League,” German Iowa and the Global Midwest. Misspellings and other errors in the original text. All of the letters quoted here are made available by German Iowa and the Global Midwest, a public humanities project housed at the University of Iowa. The homepage of the project is at https://germansiniowa.lib.uiowa.edu. Subsequent citations for images from this collection cite only the URL where they can be found.

(4) https://germansiniowa.lib.uiowa.edu/items/show/1779.

(5) https://germansiniowa.lib.uiowa.edu/items/show/1802.

(6) https://germansiniowa.lib.uiowa.edu/items/show/1778.

(7) https://germansiniowa.lib.uiowa.edu/items/show/1792.

(8) https://germansiniowa.lib.uiowa.edu/items/show/1774.

(9) https://germansiniowa.lib.uiowa.edu/items/show/1782.

(10) https://germansiniowa.lib.uiowa.edu/items/show/1795.

(11) https://germansiniowa.lib.uiowa.edu/items/show/1791.

(12) https://germansiniowa.lib.uiowa.edu/items/show/1788.

(13) https://germansiniowa.lib.uiowa.edu/items/show/1787.