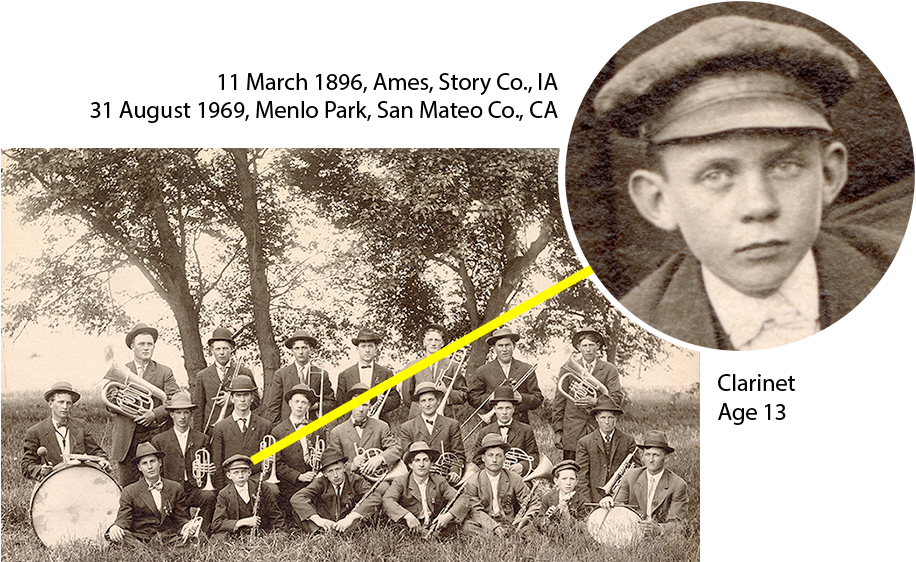

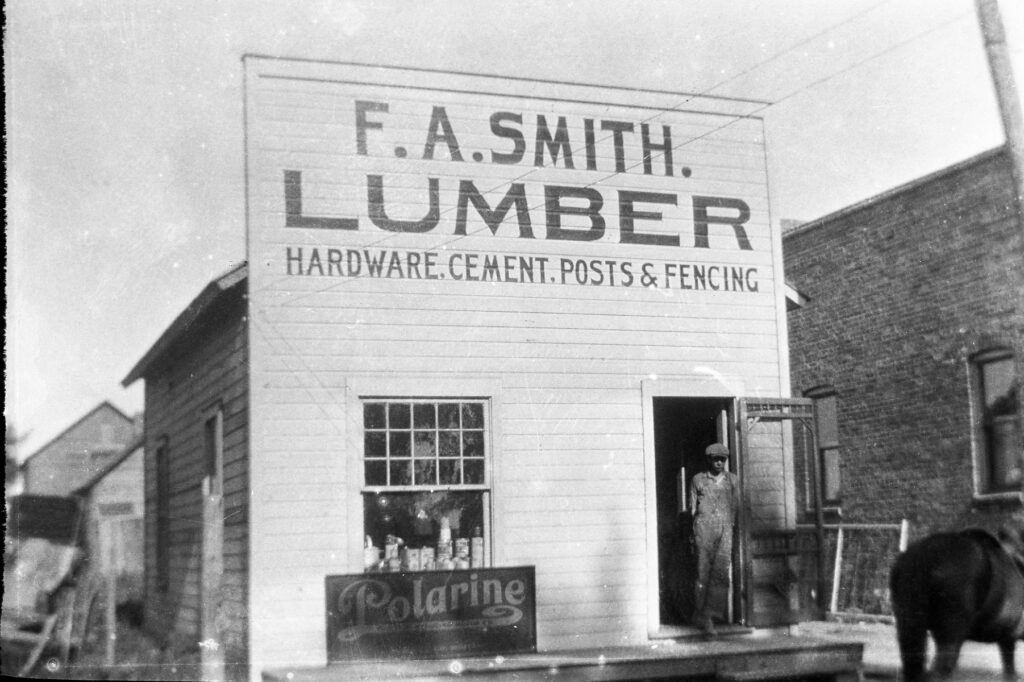

Earl Frederick Smith was born in 1896 to Fredrick A. Smith (1873-1951) and Tilleta “Tillie” Johanna Taig (1874-1961), in central Iowa, but by 1900 the family had moved to O’Brien County, where Fred managed a lumber yard in Calumet.

Fred had been born in Germany; although Tillie had been born in Iowa, her parents both came from Norway. Earl was the firstborn child of four; the other siblings were Alvin Herbert Smith (1900-1968), Maebelle Lorraine Smith (1906-2001), and Kermit Lowell Smith (1909-1977). The family later moved back to central Iowa, to Polk County, where Fred Smith opened his own lumber yard in Fort Des Moines.

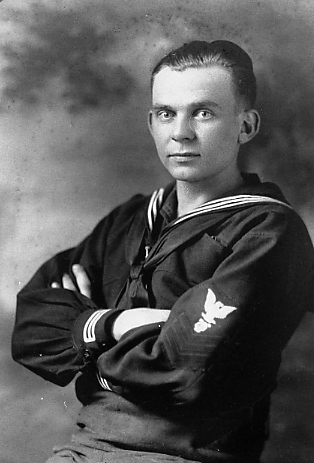

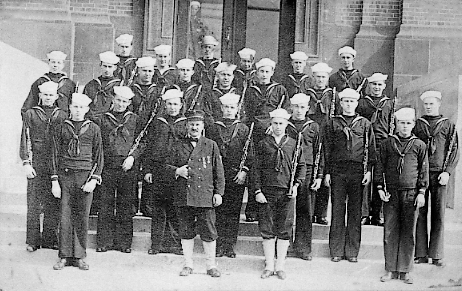

Earl Smith was one of four Calumet German Band members to serve in World War I. (The others were Newell Bidwell, 1896-1918, John Brumm, 1894-1956, and Emil Propp, 1891-1969.) Smith served as a quartermaster (rank QM1c) in the U.S. Navy, enlisting on 11 September 1916 and serving until 2 February 1920.

Unusually, Smith made further use of his musical skills during the war. He played in the “Clarinet Corps” of the U.S. Naval Reserve Band under famed bandmaster John Philip Sousa (1854-1932). Although Sousa was near retirement age at the time of the war, his fame and patriotic fervor were such that the U.S. commissioned him as a lieutenant in the Naval Reserve shortly after the country entered the war in 1917.(1)

Upon the disbanding of the “Clarinet Corps,” Earl Smith spent the remainder of his navy career raising carrier pigeons for the war effort;(2) in fact, following his wartime service, Earl retained the hobby of raising pigeons for the remainder of his life.

Shortly after the end of the war, while he was on leave from the Navy, Earl married Hazelle Frances Antoinette Rarick (1902-1995) on 22 November 1918, in Des Moines (Polk County). Hazelle had been born in Barry County, Michigan, to Frank Henry Rarick (1854-1941), who had been born in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, and Elizabeth Meyer (1860-1938), born in Lower Saxony, Germany.

Earl and Hazelle lived briefly in the District of Columbia, where Earl worked as a caretaker of a country estate near Washington. There the couple’s first child, Earl Frederick Smith Jr. (1919-1988), was born. The 1920 census shows the young family to be living with Earl’s parents, back in Polk County, Iowa. They later established their own household in that county, where their second child was born (Franklin Rhys Smith, 1924-2005). In 1925, in order to join Hazelle’s parents, who had purchased a farm in the San Francisco Bay area, Earl and Hazelle followed them there with their two children, and they went on to have a third child, Elizabeth Marylee Smith (1928-2015).

Living initially in the Carmel/Salinas area (Monterey County) and later in San Mateo County, further north in the Bay Area, Earl embarked on an interesting and locally famous career. After working briefly with the California State Parks Department and then managing a large wholesale nursery, Earl opened his own nursery business. In taking this step, he capitalized on and furthered an intense interest in plants and horticulture that he had had since youth. In a local publication, he was quoted as saying, “I had my own hot bed ‘way back at the tender age of 9, in the days when good horse manure was used as the main source of ‘radiant’ heat.” He also opened a pest control business, called Plantsmith, which advertised with the jingle, “To shoe a horse see a blacksmith. To shoo the bugs see Plantsmith.” In 1939, he introduced a plant food, Spoonit, of his own formulation, which achieved wide commercial success.

Shortly after the outbreak of World War II, Earl built on this horticultural expertise by taking a position as Manager of Research Greenhouses with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Emergency Rubber Project.(3)

After the war, Earl continued his well-known nursery and commercial fertilizer sales businesses, occasionally also lecturing at a local university and elsewhere on horticultural topics, until he fell into ill health around 1960. Following his death in 1969, his wife Hazelle lived on into her early 90s.

Of the Smiths’ children, two — Earl Frederick Smith Jr. and Franklin Rhys Smith — remained on the West Coast, and the youngest child, Elizabeth Marylee Smith, relocated to Cook County, Illinois.

Earl Frederick Smith and Hazelle F. A. Rarick Smith are buried in Alta Mesa Cemetery, Palo Alto, California.

Subscribers to Ancestry.com may wish to further explore some family connections of Earl Smith by accessing an Ancestry profile page (within the context of a “Mugge Family Tree”).

Connection to Other Band Members

In the case of Earl Frederick Smith, there are no known family or other close connections to other Calumet German Band members.

Footnotes

(1) The value of having Sousa involved with stateside war efforts clearly represented a public relations coup on the part of the U.S. Navy. The Naval Reserve Band was based at the Great Lakes Naval Station, north of Chicago. During this time, Sousa donated his Navy salary to the Sailors’ and Marines’ Relief Fund. After the war, he returned to conducting his own band, but for the remainder of his life he often wore the Navy uniform during band performances.

(2) One surprising detail about military efforts during WWI and even into WWII is the use of homing pigeons and carrier pigeons for several types of communication tasks — a strategy that had a centuries-long military history. On the European battlefields of WWI, the French and British armies used pigeons to relay messages (carried within leg canisters) from frontline troops back to a stationary base. In the final year of the war, the U.S. Navy exploited the strong homing instincts of pigeons to send messages from aviators under conditions when the use of radio might be dangerous or impossible. In one scenario, birds were carried on aircraft and released in the event that a plane crashed, especially when over water; when the pigeon flew back to the base, a search crew was dispatched to rescue the pilot and crew if possible. The U.S. Navy’s Pigeon Service bred, trained, and transported a flock of some 2,500 birds.

(3) This project is fascinating in itself as a wartime effort to diversify the sourcing of a raw material essential for the production of armed forces matériel. The U.S. was dependent for military vehicles on natural rubber, produced by the latex of rubber trees (Hevea brasiliensis) in Southeast Asia. Irrespective of wartime needs, natural rubber is problematic because Hevea brasiliensis is vulnerable to disease and parasites, but once the Japanese successfully cut off global supplies of rubber during the war, it created a crisis. The U.S. government established the Emergency Rubber Project, led by scientists from Caltech, in an effort to extract rubber from guayule (Parthenium argentatum), a wild shrub that is native to the U.S. Southwest. A second initiative, the Manzanar Guayule Project, aimed to genetically engineer better strands of the shrub and then to achieve mass production. This project, based at the now infamous WWII-era Manzanar internment camp, had the aim of both involving the talents of Japanese Americans interned at the camp, including Japanese-American scientists, and utilizing a captive (as it were) workforce for the agricultural aspects. While the project successfully produced several hundred tons of rubber from guayule, the war ended before the effort could achieve full sustainability. Even today, while synthetic polymers are used for many applications that traditionally relied on rubber, the superior chemical properties of natural rubber make it essential for products such as heavy-use tires.