The musical context of the Calumet German Band might provide the most obvious point of departure for discussing the 1909 photo. It’s a band, after all, and the 22 young men and boys are holding their instruments: six cornets, four trombones, three mellophones, two tubas, four clarinets, two drums, and a piccolo.

And yet for many obvious questions — What did the band play? How did it sound? Where did it perform? Where did it rehearse? How long did it exist? — answers are unlikely to be found. Little is known for certain, and the historical record comes up short.

Genesis of the Band

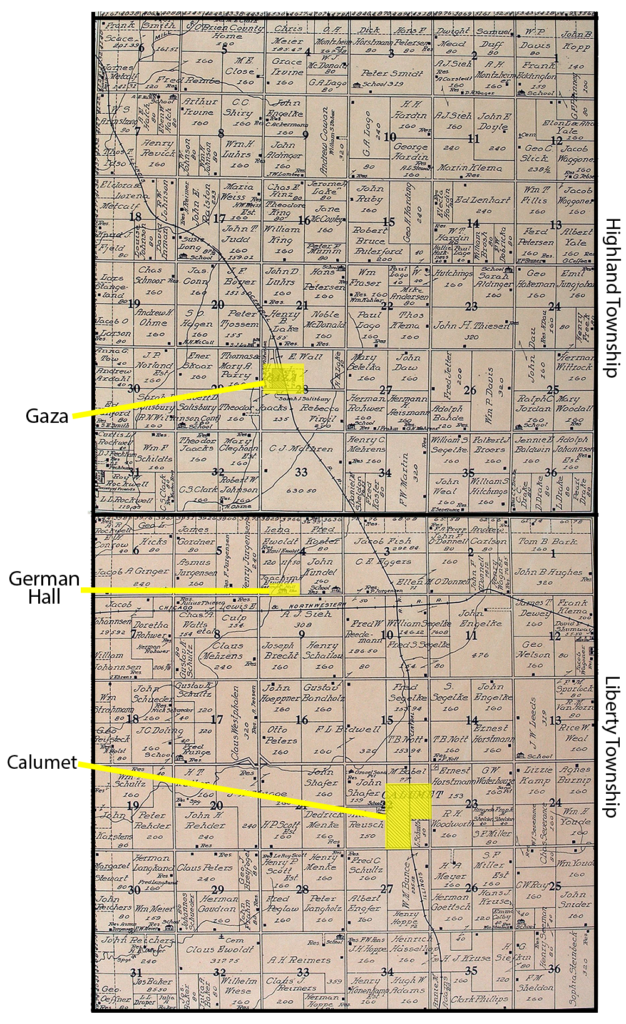

As discussed also in the biosketch for band director Ralph E. Langley (1880-1977), a short entry in Langley’s hometown newspaper, The Decatur [Nebraska] Herald, on 27 February 1908, reprinted an item from The Primghar [Iowa] Bell(1). It read, “R. E. Langley went to Gaza Saturday night and conducted the first practice of the new Gaza band[,] he having been engaged as leader and instructor. He reports a very promising organization of about twenty pieces.”

The description of a “new Gaza band” reflects the fact that the small Liberty Township towns of Gaza and Calumet were only a few miles apart. Some of the band members lived on farms closer to Gaza, and others on farms closer to Calumet and in the town of Calumet. Probably only later in 1908 or in 1909 did the band identify itself as the Calumet German Band.

In 1914, a local history book reported this:

A good brass band was organized here a few years since, consisting of twenty-two pieces. It was formed and is instructed by the foreman of the Primghar Bell, Ralph Langley. It is a credit to the vicinity. – 1914 O’Brien County history book(2)

Here there was a slight inaccuracy, but a revealing one. The band was not solely a brass band, as it comprised winds and two drums in addition to a variety of brass instruments. But the reference reflects a widespread cultural phenomenon. There were numerous brass bands in 19th- and early 20th-century America, and Ralph Langley had become familiar with such bands as a youth, growing up in a household that was filled with music and instruments. In this era, community bands of all flavors — brass bands, wind ensembles, military and concert bands — provided cultural identity, the opportunity for civic participation and community building, relaxation from hard lives, and wholesome entertainment. Almost every small town in the country boasted a community band of some sort. In the first decade of the 20th century, within just a 20-mile radius of Calumet, the towns of Sutherland, Paullina, and Primghar (O’Brien County) as well as Larrabee (Cherokee County) and Royal (Clay County) all had community bands, with some identified as “cornet bands.”

The age profile of the Calumet German Band (mean age 19.2 years) has additional relevance, because amateur musical groups like this one also provided a benign outlet for youthful energy. They were the garage rock bands of the time.

Already as a 15-year-old, Ralph Langley wrote of belonging to the Decatur Silver Cornet Band. For many regional cornet bands in this era, their identification as a “silver” band was a point of pride. Instrument makers applied thin silver plating in an electroplating process; although such instruments are more expensive, the plating offers the aesthetic pleasure of a brilliant sheen that can be polished just as other silver.(3)

Musical Training and Proficiency

What kind of musical skill did the young men in the Calumet band possess? Where did they acquire it? Again, solid answers are impossible because the available evidence is lacking.

None of the band members had had formal, professional musical training. But it is important to remember that in an era without modern entertainment options — no TV, Internet, or smartphones, no PlayStations or Wii consoles — music-making was often part of the shared activities of European and American families alike, and familiarity with a musical instrument was valued for children in these families.

The leadership of Ralph Langley would also have been critical. In other circumstances, both before and after his involvement with the Calumet German Band, Langley is known to have served as an instructor as well as an ensemble director. Langley would have helped to train the band members on their instruments — he was proficient on a number of them — and for any members who could not read music or had limited music-reading ability, he would have insisted on teaching them.

Venues and Band Tenure

The 1908 newspaper item about Langley’s travel to Gaza offers a clue about the band’s early activities. As can be seen on the 1911 map of the area (see above), the German Hall (also known as Liberty Township Hall) — two and a half miles from Gaza — would have been a likely location for the group to meet and rehearse.

As a facility built to serve Liberty Township and adjacent areas, the German Hall was the venue for dances and other social activities throughout the early decades of the 20th century. Items in The Sutherland Courier report the Calumet German Band playing there, but more frequently the paper reported that the band performed in Calumet, where presumably the venue was the town hall, which had been built in 1889-1890. The hall had a stage and seated 300 people.

A Sutherland Courier item on 13 May 1910 reported that the band had recently acquired uniforms:

Calumet News

Next Saturday, commencing at 8:00 o’clock, the Calumet German band will give a program of songs, readings, and instrumental solos, as well as selections by the band. This will be the band’s first public appearance in their new uniforms and they invite you to come and see them. A dance will be held in the hall at the close of the program. Admission at 10 and 25 cents. They will also give a free open air concert at 7:00 p.m.

It seems that open-air concerts were the predominant venue for band appearances. One such location would have been Calumet’s town park, a one-square-block area that had been laid out in 1906. And the band traveled to nearby towns for holiday concerts and other occasions, as evidenced by Sutherland Courier news items:

The Calumet German Band played at Cherokee Friday for the big picnic that was given by the Yoeman(4). (20 August 1909)

The Calumet German band will give a free open air concert in the [Primghar] court house park next Saturday evening. A week later the Primghar Commercial club band will go to that place and play a return concert. (18 August 1911)

Although it looked as if it might rain Tuesday forenoon, it came out fine in the afternoon and a large crowd gathered in Gaza to have a good time at the Farmers’ picnic. Good music was furnished all day by the Calumet German band. (7 June 1912)

The Calumet Band furnished the music for the Memorial Day festivities at Primghar, and Primghar citizens will soon be aware of the fact that Calumet has one of the best bands in this part of the state. (3 July 1913)

Come to Calumet July 4 and we’ll show you a good time. The day’s doin’s will commence at 9:30 with a street parade, headed by the Calumet German band, who will play throughout the day. Dinner and refreshments will be served by the German Ladies’ Aid society; at 1:30 the Gaza and Calumet ball teams will cross bats, after which will come the street sports and trap shoot. At 7:00 o’clock the band will give a concert. A little later in the evening there will be a display of fireworks and a big dance in the evening. (3 July 1913)

On 28 August 1913, the Courier reported that the band would be offering street concerts in Calumet “for the balance of the summer.” Performances after 1914 cannot be documented, however, leaving the impression that the group was most active for a period of six years, from early 1908 to late 1913.

The Music

Because no sheet music used by the band is known to have survived, it is difficult to answer the question of what type of music it played. Community bands in this time and place would have performed a variety of light, popular fare for entertainment and social purposes, rather than serious concert music such as that performed in concert halls in urban centers by professional ensembles. Evidence from newspaper items such as those quoted above indicates that instrumental solo and small-ensemble works would have been interspersed with works for the entire band.

As a self-identified “German” band, the group would have embraced the culture of the band members, performing popular tunes and ditties that were known and loved by the German-American residents of Calumet and Liberty Township, who overwhelmingly had emigrated from the Schleswig-Holstein region, as discussed in the previous section, “The Cultural Milieu.”

Additionally, Ralph Langley’s family upbringing and his earlier experience with brass bands would surely have influenced the repertoire choices. The Langley family cherished American patriotic songs and military marches, especially those of John Philip Sousa (1854-1932), the famous “March King” of the decades spanning late 19th- and early 20th-century America.(5)

Sousa had achieved great fame with his Sousa Band, which performed on nearly 16,000 concerts between 1892 and 1931 while on tour in the U.S. and worldwide. As a result of the popularity of these concerts in far-flung regions of the country, many community bands were established on the model of the Sousa Band.

Patriotic songs and/or marches would also have figured in the Calumet German Band’s appearances at civic gatherings. One such gathering, a political rally in October 1912, is discussed in the section below on musical instruments.

Finally, as noted above, the band would have played at Liberty Township’s German Hall, known to function as a dance hall. Thus, popular dance music genres within German culture at this time — galops, schottishes, waltzes, and others — would have figured into the band’s repertoire. The galop, a country dance in 2/4 time, was a forerunner of the polka that then arose in Czech and Polish regions of Europe but underwent many regional and cultural variations throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. In a later guise, polka music was typically performed by small ensembles (perhaps only three or four players) that would have included an accordion or concertina — notably absent from the Calumet German Band. But according to curators at the National Music Museum(6), this absence does not mean that the band did not play polkas. Other community bands in this era, of similar instrumental makeup, were known to have included polka music in their musical lineup, and its inclusion would have endeared the Calumet German Band to many members of the community.

The Instruments

Nonmusicians, and even some professional musicians, may be surprised to learn that the precise identification of instruments — even categories of instruments — from a historic photo is difficult if not impossible. The world of band instruments is complicated, and those in the Calumet German Band fall into more nuanced categories than simply woodwinds and brass.

Because music-making was valued within this culture, musical instruments at the time were affordable and easy to acquire, consumer options were numerous, and instrument makers were proliferating and producing new models every year. For example, soon after Richard W. Sears and Alvah Roebuck established their mail-order catalog business in 1887, inexpensive musical instruments quickly became a money-making category within the new Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalog.

Again, Ralph Langley’s role was important because he was a source of musical instruments as well as expertise. It is virtually certain that he supplied instruments to Calumet German Band members as needed. Beginning in his youth and extending throughout his life, Langley frequently shared and traded instruments with family members (his father, Robert G. Langley, and the family of five brothers all played instruments), and he is known to have supplied them to other bands with which he was involved. He had a special fondness for brass instruments produced by C. G. Conn Ltd., which at this time was becoming a preeminent producer in the U.S. and globally.(7)

The Band’s Piccolo

The piccolo (sounding an octave higher than a standard transverse flute) played by 12-year-old band member Newell Bidwell is the easiest instrument to identify and discuss because unlike almost all other Calumet band instruments it is actually available for inspection.(8)

A close look shows that it was produced by Lyon & Healy, a well-known Chicago instrument maker and distributor.(9) The body is probably grenadilla wood, a hardwood that is still often used to make piccolos (modern instruments might also be made of silver or metal alloys). The head joint, of milled and polished ivory, is lined with a metal sleeve, the purpose of which is to produce a more brilliant, penetrating sound than that produced by ivory (or wood) alone. The instrument is fitted out with six keys, a common setup at the time. The keys and other fittings are probably a nickel-silver alloy (called maillechort).

Piccolos of this size often would have been supplemented by a separate mouthpiece, called a fipple, that would make the instrument easier to play. The fipple, which was clamped onto the head joint, enabled the performer to play the piccolo like a recorder or tin whistle — rather than having to form a precise embouchure with the lips to blow at the correct angle across the small hole itself. Newell Bidwell’s piccolo, however, was not fitted out with a fipple mouthpiece. The small stature of 12-year-old Newell Bidwell would certainly have offered an advantage to him: the diminutive size of the instrument, the tiny hole in the head joint, and especially the small, closely spaced keys would have been much more difficult for an adult — and certainly for a nonprofessional — to negotiate. Newell’s small hands and mouth came in handy for the Calumet German Band.

“H.P.,” and Pitch Standards

Notably, Newell Bidwell’s piccolo is stamped with the letters “H.P.” — “high pitch.” Today, musical pitch (“concert pitch”) is generally (although not always) standardized at a physical frequency of A=440, meaning 440 hertz (Hz) for the sounding of the A above middle C (sometimes called A4) on a standard piano.

This is a modern convention.

Prior to the 20th century, there was no recognized standard pitch; the tuning of an orchestra or other ensemble was a localized concept and wildly variant, sometimes even within a single European city, and sometimes even within a single church (because of the way organs were tuned, which over time necessitated organ pipes to be trimmed down, raising the overall pitch of the instrument). During some historical eras there was even a phenomenon of “pitch inflation,” by which instrumentalists would play almost imperceptibly above pitch in an attempt to produce a more brilliant, soloistic sound.

Over the centuries, attempts at reform and standardization were only partially adopted, and in fact a more successful reform was a direct and surprising outcome of World War I. Embedded within the Treaty of Versailles that ended the war is a section by which the parties enshrined an 1885 European convention enforcing an international standard for pitch — perhaps in a mild echo of the biblical injunction (Isaiah 2:3-4) to turn swords into ploughshares, or Great War armaments into uniformly pitched piccolos.

Nevertheless, fixed-pitch instruments like organs, especially historic instruments in Europe, problematically limit the enforcement of an absolute, internationally recognized standard. And even today, some European orchestras tune to a slightly higher pitch than do orchestras in the U.S. and elsewhere.

For the Calumet German Band, although it did not include a fixed-pitch instrument like an organ, harmonium, accordion, or piano, it did include Newell Bidwell’s H.P. piccolo — perhaps pitched as high as A=458 — which meant that other players had to adopt that pitch also. It is unknown whether any of the other instruments were specifically designed as H.P., but brass instruments and clarinets are tunable within a somewhat narrow range.

The Brass Instruments

Much less information can be provided about the remaining instruments in the Calumet band, because it can be gleaned only from the photograph itself. However, it does appear that the brass players all have silver-plated instruments rather than instruments covered in lacquer alone. Charles Bandholz’s tuba and Ralph Langley’s cornet are known to have been silver-plated. Even as a youth, Langley was proud of owning a silver-plated cornet and playing in a “Silver Band” (see above), and he would have been a ready source of such instruments for Calumet band members.

Cornets

The cornets in the band are of different size and shape, indicating that larger ones might be pitched in B-flat and other, shorter instruments might be pitched in E-flat. Note that in general, cornets are shorter and more compact than trumpets, and their bores are more conical than the more cylindrical trumpet bores. There has always been a wide variety of both instruments, and they may be pitched in more than a half dozen keys, necessitating transposition on the part of the player. Like all musical instruments, cornets have undergone constant evolution and refinement in design over centuries.

Not all of the six cornets in the Calumet band (John Brumm, Henry Friedrichsen, Ralph Langley, Emil Propp, Harry Rochel, and Allie Sohm) can be clearly disambiguated from the photo alone because some are partially hidden. But three instruments provide good comparisons. The cornet played by Harry Rochel is clearly shorter and more compact than that played by Allie Sohm, indicating that Rochel’s is probably an E-flat instrument. And the instrument played by Henry Friedrichsen is altogether different from the others; its size and bell shape indicate that it might be a flugelhorn, front-bell alto horn, or bass trumpet rather than a cornet like the other instruments.

Tubas

The two tubas in the band are also of different size. Because the tuba played by Charles Bandholz is still in existence — it was handed down to Charles’s son Clarence and then to grandchildren — it can be identified as an E-flat “Champion Silver Piston” from Lyon & Healy, the well-known Chicago instrument maker and distributor mentioned above in the discussion of Newell Bidwell’s piccolo.(9)

Charles Bandholz’s tuba can be seen to be larger than that of Herman Steinbeck, which is smaller and closer to a euphonium-type or baritone horn, with smaller bell flare and bore size.

See also the Charles Bandholz bio page for a photo of Bandholz’s tuba in a later decade along with his son, Clarence Bandholz.

Trombones

The four trombones appear to be of the same general type, but they may differ in size (length) and/or bore diameter. The instrument used by John Rohlf seems slightly smaller than those used by Nick Jessen, Albert Mehrens, and Ernest Shafer, possibly indicating an alto trombone rather than a tenor trombone. Rohlf is also using a funnel-shaped mouthpiece rather than the cup-shaped mouthpiece used by the three other players, although this may be a matter of player comfort rather than for reasons of tone quality.

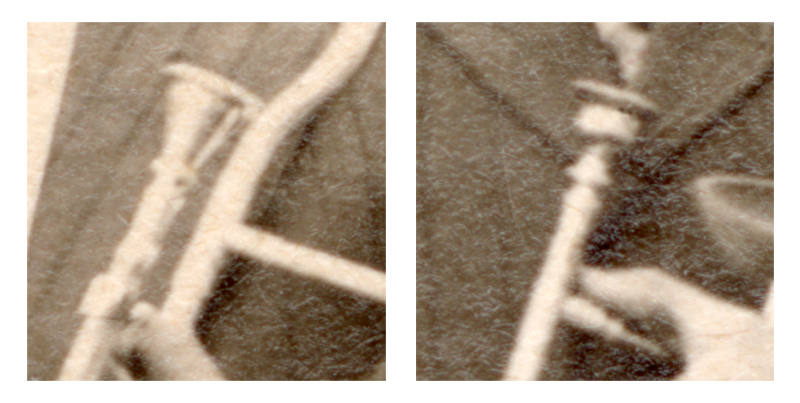

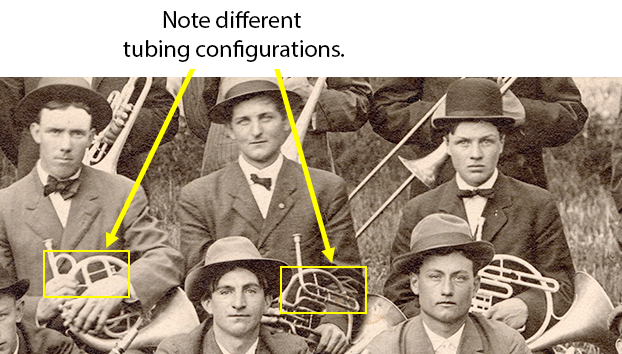

Mellophones

The three horn players (Henry Lorenzen, Henry Mugge, and William Shafer) are actually playing traditional mellophones, with piston valves, pitched in E-flat or F, rather than French horns. The mellophone has a somewhat more reduced tubing system than a French horn, although the musical range of the instrument is similar. The instrument used by William Shafer has a slightly different configuration than the other two horns, which may indicate only that it comes from a different maker.

Clarinets

Again, partial views in the photo do not provide sufficient clarity to indicate the types of instruments used by the four players (Henry Andersen, Charles Rochel, Hans Sievers, and Earl Smith), but the keywork installed on the instruments shows that they all used the “Albert” fingering system (sometimes called the “simple system”) rather than the “Boehm” system.

All woodwind instruments use a complicated array of keywork, and the fingering necessary to deploy it, to close and open holes in the instrument so that different notes will sound. Over the centuries, different systems for all of the woodwind instruments have been developed, with different aims in mind.

The Boehm system for clarinet, dating from the first half of the 19th century(10), improved on what had previously been an unwieldy instrument by adding more intricate and sophisticated ring keys and needle springs. As a result, the remodeled instrument had better tone and intonation, and a more logical fingering system made it possible for players to become more virtuosic and achieve greater accuracy. But although Boehm’s improved keywork and fingering system for the flute had made that instrument easier to play, the system as applied later to the clarinet is best suited for professionals. The Albert or “simple” fingering system, developed by the 19th-century Belgian woodwind instrument maker Eugène Albert (1816-1890), remains the more suitable system for amateur clarinet players (and additionally it is sometimes preferred by musicians performing certain folk styles). These types of instruments are also less expensive than clarinets configured with Boehm keywork.

Drums

The two drums in the band (John Mehrens, bass drum, and William “Bill” Eggers, side drum) are for the most part unremarkable, although both can be seen to have metal tension rod systems, indicating a higher-quality drum. Note that the bass drum has a cymbal on a mount.

Additional Brass Instrument Seen in 1912

A second photo representing the Calumet German Band (although only a subset of members) captures the band’s role at a political rally in Primghar, Iowa, on 15 October 1912.(11)

In addition to illuminating the turbulent politics of this era (see footnote), the photo provides musical insight in that it shows a brass instrument that was not in evidence in the 1909 photo. A bandmate in the front row is holding what is probably a tenor or alto horn (the names are synonymous), which he evidently acquired sometime after 1909. The alto/tenor horn (called an Althorn in Germany), which is usually pitched in E-flat, is part of the saxhorn family of instruments; it has a mellow timbre and is in the mid-range of the brass instruments.

The photo also offers the only known photographic evidence of the band’s uniforms, acquired in 1910. Bandmates can be seen wearing military-style caps with visors, and the uniforms’ jackets can be glimpsed underneath the winter coats of a few players.

The next section, “Band Member Bios,” provides biographical snapshots of all 22 Calumet German Band members.

Footnotes

(1) Later The Primghar Bell became the O’Brien County Bell, and in more recent years it consolidated with other local newspapers and is now known as O’Brien County’s Bell–Times–Courier.

(2) Past and Present of O’Brien and Osceola Counties, Iowa, by Hon. J. L. E. Peck and Hon. O. H. Montzheimer (for O’Brien County) and Hon. William J. Miller (for Osceola County). Vol. I. Illustrated. Indianapolis, IN: B F. Bowen & Company, Inc., 1914.

(3) Brass instruments (which may be made of yellow, gold, or red brass) benefit from some type of finish to protect the underlying metal from acids in the perspiration of the player. This may be a lacquer or silver (or an alloy), but in the era of the Calumet German Band, silver seemed to have a special prestige. Aside from the aesthetic reasons, some musicians and instrument makers profess that silver and lacquer produce different tone qualities (lacquer said to produce a more mellow tone, and silver more brilliant), but this is controversial. Brass instruments may also be raw metal (uncoated, unlacquered), but such instruments will eventually dull and develop a patina (which again may be preferred, for various reasons). Likewise, modern flutes can be made with a variety of body and plating materials (nickel, silver, gold, platinum, or alloys such as nickel-silver), and the advantages and disadvantages of each are subjective and a matter of debate among professionals.

(4) “The Yoeman,” possibly a misspelling of “Yeoman” although spelled “Yoeman” in repeated Sutherland Courier mentions, seems to have been a small, local fraternal lodge.

(5) Interestingly, one of the Calumet German Band members, clarinetist Earl F. Smith (1896-1969), later played under the bandmaster in the “Clarinet Corps” of the U.S. Naval Reserve Band during Smith’s service in World War I. John Philip Sousa’s fame and patriotic fervor were such that the U.S. commissioned him as a lieutenant in the Naval Reserve shortly after the country entered the war in 1917. The value of having the eminent man involved with stateside war efforts clearly represented a public relations coup on the part of the U.S. Navy. Sousa’s Navy Band was based at the Great Lakes Naval Station, north of Chicago. During this time, Sousa donated his Navy salary to the Sailors’ and Marines’ Relief Fund. After the war, he returned to conducting his own band, but for the remainder of his life he often wore the Navy uniform during band performances. Sousa composed more than 130 marches and numerous other works, such as band arrangements of well-known 19th-century symphonic works.

(6) Personal communication, Dwight Vaught, NMM Director. The National Music Museum is a world-renowned museum and research institution with collections numbering more than 15,000 musical instruments and related objects as well as curatorial expertise in a wide variety of string, woodwind, keyboard, and brass instruments. The museum is located in Vermillion, South Dakota, and is a partnership between an independent, nonprofit organization and the University of South Dakota, through which it also offers a master’s degree program. https://www.nmmusd.org.

(7) Charles Gerard Conn (1844-1931), who after his Civil War service was a grocer in Elkhart, Indiana, and an amateur cornet player, started to make advances in brass instrument design and then enter into instrument manufacturing and sales beginning in the 1870s. With the help of like-minded business partners, and through successive company iterations, Conn and his colleagues were able to attract experienced European craftsmen to help perfect instrument design and fabrication. By 1905, C. G. Conn Ltd. had the world’s largest musical instrument factory, and it had expanded beyond brass instruments to a full line of wind and string instruments, drums and other percussion instruments, and portable organs. Conn and his company managed also to transform the area of Elkhart, Indiana, which became a magnet for other instrument makers; several dozen such companies were based there in the mid-20th century, the heyday of U.S. musical instrument manufacturing. Although in the decades after Conn established his company it would be reorganized and undergo mergers and acquisition by other corporations, the germ of the company still exists today within the Conn-Selmer division of Steinway Musical Instruments. A colorful figure who experienced mid-career fame and wild financial success, Charles G. Conn parlayed his business skills into a political career (serving for one term as a U.S. congressperson for Indiana) as well as newspaper publishing and other (sometimes dubious) endeavors. But he subsequently experienced personal crises, divorce, public scandal, and business failures. Upon his death in 1931, when he was near penniless, employees of the Conn factory took up a collection to pay for his grave marker.

(8) It has been lovingly preserved through the years by the Bidwell family and for the last several decades by Cinda Bidwell Beardsley.

(9) The Lyon & Healy Company, established in the mid-19th century and still thriving in the 21st century, is a storied Chicago musical instrument supplier and manufacturer with an interesting history. The company has produced a variety of instruments over the years, and it also has been in the business of distributing instruments produced in Europe. Lyon & Healy was established by George Washburn Lyon (1825-1894) and Patrick Joseph Healy (1840-1905), who opened a first store in Chicago in 1864, selling the sheet music of Boston publisher Oliver Ditson. A fire destroyed the company’s store in 1870, and after reopening, the store was destroyed again in the Great Chicago Fire of October 1871. The company recovered from these disasters, and soon it expanded into instrument sales and manufacturing, also entering into a relationship with Steinway & Sons, the famous New York piano maker. Over the next decades, Lyon & Healy became nationally and then globally prominent. In the late 19th century, the company was producing a variety of instruments, and it was an even more important importer and distributor of high-quality instruments from European makers. But harp making became the company’s primary business, beginning in 1889. Lyon & Healy had its own two-story pavilion at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where it presented its wares and offered daily concerts. By the end of the 19th century, Lyon & Healy had become known as one of the world’s most esteemed makers of harps, and it ended its other lines of instrument production in 1925. Following several changes in corporate ownership beginning in the 1970s, the Lyon & Healy Harps brand was acquired in 1987 by Salvi Harps of Italy. https://www.lyonhealy.com.

(10) Although the system is named for Theobald Boehm (Böhm) (1794-1881), who had devised an improved keying system for the flute, Boehm was not involved in the keying system for the clarinet, which was developed by Hyacinthe E. Klosé (1808-1880) and Louis-Auguste Buffet (1789-1864).

(11) In the 1912 election year, Theodore Roosevelt was running for president on a third-party ticket — the Progressive Party, popularly known as the “Bull Moose” Party. Following Roosevelt’s two presidential terms (1901–1909), his handpicked Republican Party successor, William Howard Taft, came to become a political rival by failing to implement the “Square Deal” progressive policies that Roosevelt had promulgated during his presidency. Roosevelt challenged Taft for the 1912 party nomination (there was no prohibition against a third presidential term prior to enactment of the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution in 1951), but Taft narrowly won the nomination. Roosevelt then created the Progressive Party to oppose both Taft and Democratic Party nominee Woodrow Wilson. Although the rift between the Republicans and the Progressives ended up splitting the progressive vote and producing an electoral win for Wilson, Roosevelt’s unprecedented campaign was remarkably successful. His proportion of the popular vote was higher than Taft’s (27.4% versus 23.2%), making Roosevelt the only U.S. third-party nominee to ever outperform a major party’s candidate.

The Calumet German Band’s support for the “Bull Moose” candidacy could be expected from the overall political tenor of the times. The Progressive Party proved to be immensely popular in rural areas because its platform expressed support for farm relief and concern for the economic viability of farmers, emphasized tariff reform (lowering tariffs overall but providing protection for U.S. agricultural products), and strongly opposed big business in favor of labor rights.

On Tuesday, October 15, exactly three weeks before the November 5 election, supporters of both the Progressives and the Republicans held automobile tours of O’Brien County, with stops in several towns for rallies and speeches by congressional candidates. While the photo above was taken in the main square of Primghar (the O’Brien County seat), other stops of the band that day, as reported by The Sutherland Courier, were at rallies in Paullina and Calumet.