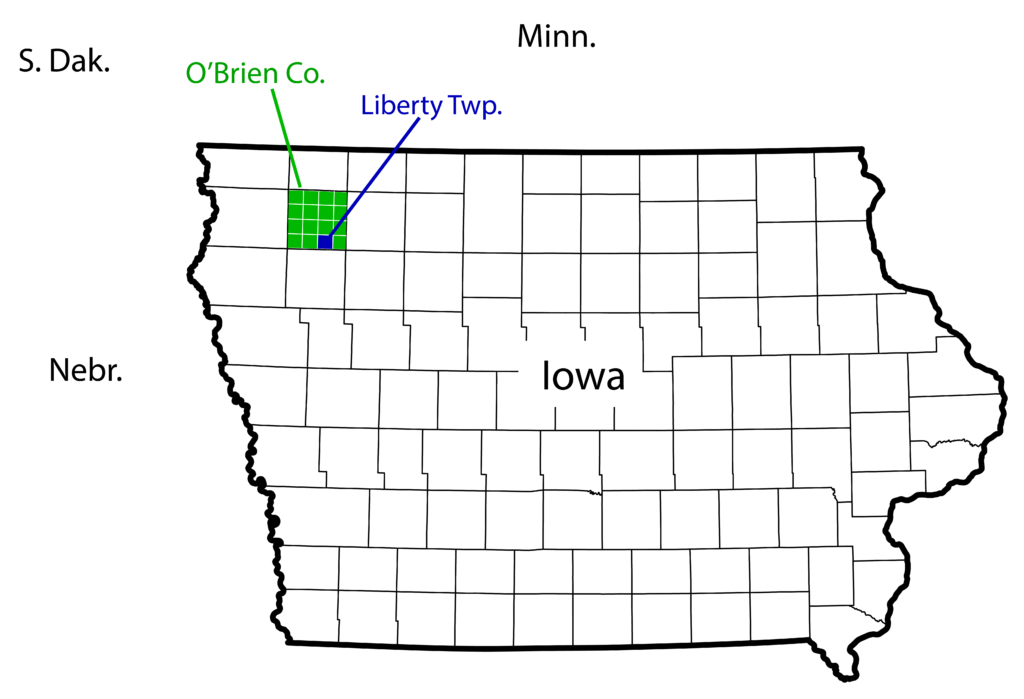

Along the southern tier of O’Brien County,(1) Iowa, the small town of Calumet lies within Liberty Township, which was organized in 1869.

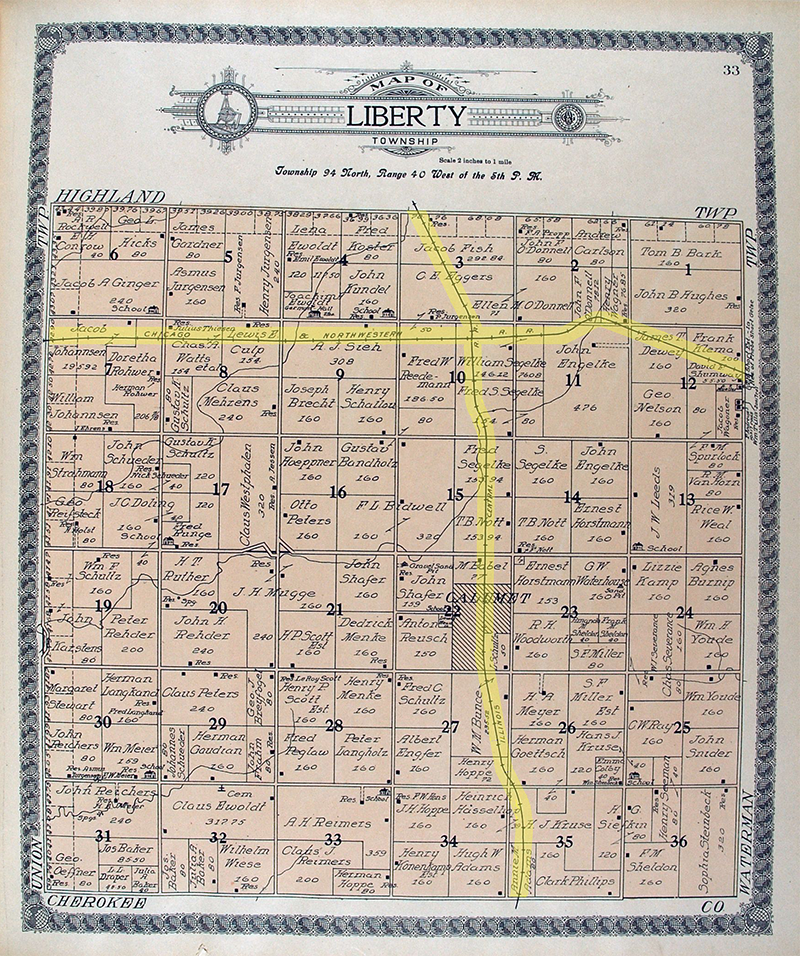

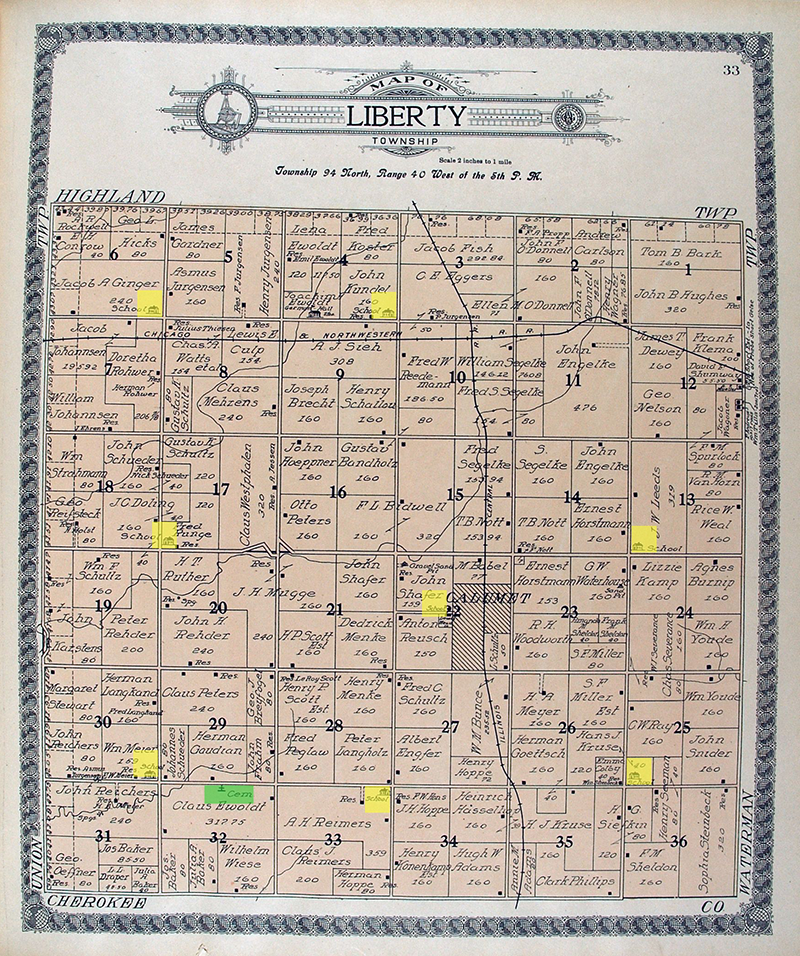

Calumet was first platted in 1887, with several enlargements made over the next two decades, and the town was incorporated in 1895. Both Calumet and Gaza (pronounced GAY-zuh), five miles to the north, owe their existence to the Illinois Central Railroad, which ran north and south through this region. The Calumet(2) railroad depot was erected soon after the laying of the track had been completed in 1887. The town of Paullina, about nine miles to the northwest, and Sutherland, less than five miles to the east, date from just a few years earlier, around 1882, when a different line, the Chicago and North Western Railway, was extended westward to these points. A 1914 history book(3) notes that “unfortunately [Calumet] is not situated at the crossing of the two railroads.” As seen on the map (above left) from a 1911 plat book, that crossing lies two miles to the north of the town.

Railroads were critically important for the late 19th- and early 20th-century development of this region.(4)

Both the Illinois Central Railroad and the Chicago and North Western Railway had received large land grants from the federal government to extend their lines into generally unsettled regions. In turn, the companies sold parcels to settlers and developers to finance the construction of the lines. For farming families who settled in these areas, the new availability of rail transport into and out of the region was an essential part of infrastructure and a spur to development. In addition, the Homestead Act of 1862 was an important mechanism in accelerating the white settlement of Iowa and other western territories. The act granted 160 acres of public land to any person who was 21 years of age or older, a head of household, and a U.S. citizen or intended citizen. This individual had to live on and improve the land for at least five years before ownership could be claimed.

The region of northwest Iowa was not empty at the time of white settlement, of course, but the Native American population was probably not large. Resident Native Americans in this region prior to the arrival of white settlers were primarily of the Sioux nation, whereas Ioway Indians were more prevalent in northern, central, and eastern Iowa.

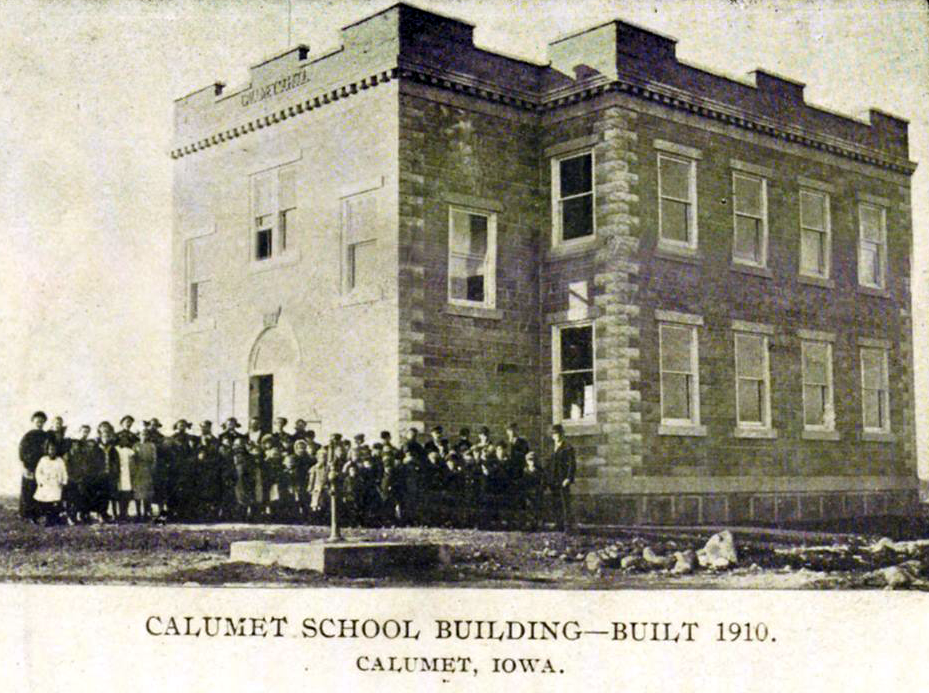

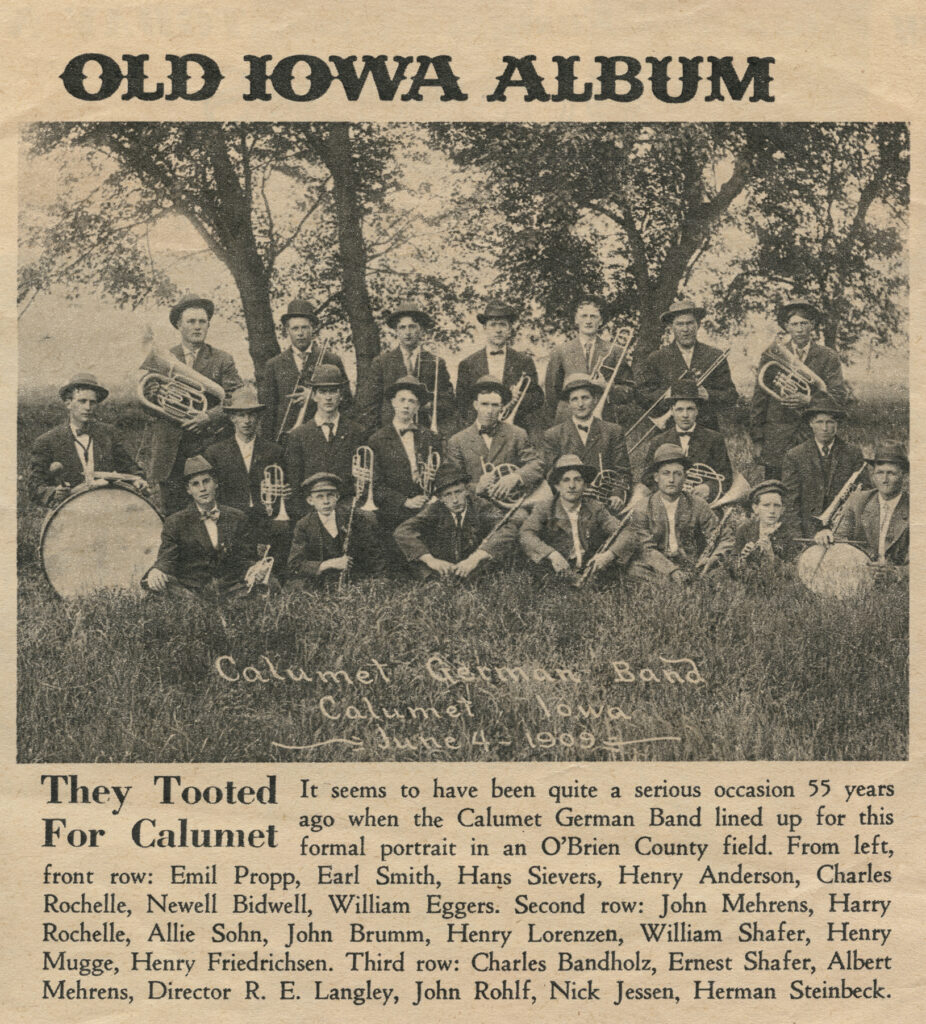

At the turn of the 20th century, there were a number of one-room country schoolhouses sprinkled throughout the township’s grid of six miles by six miles, spaced close enough together that children would not have to walk more than a couple of miles to a nearby school. But a larger, more centralized school within Calumet was being organized exactly at the time of the 1909 Calumet German Band photo.(5)

The map above at right also shows the location of Liberty Cemetery, southwest of the town of Calumet. Established soon after settler families moved to this region, and then expanded over the years, it is the final resting place for a number of Calumet German Band members and their families.

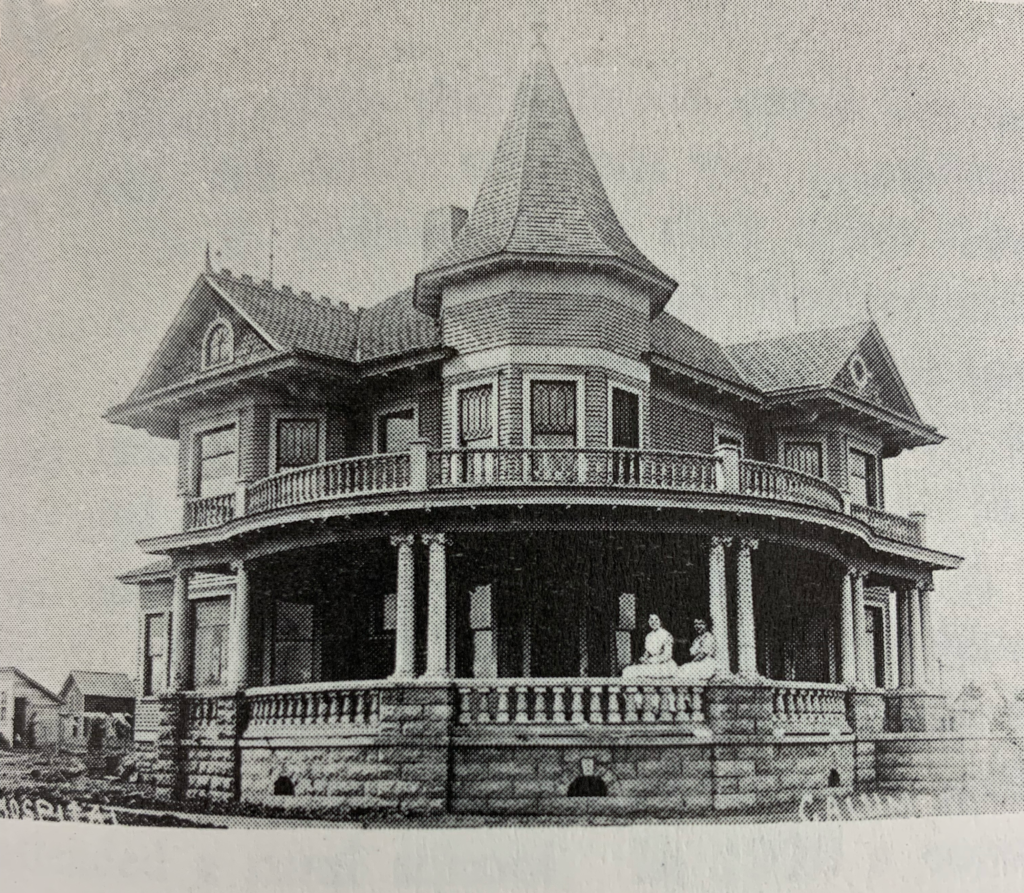

In 1897, the town suffered serious loss from a fire, but growth continued, and shortly thereafter Calumet boasted a bank and post office, newspaper, town hall, park of one square block, hotel, several retail establishments, and even a hospital with two physicians and surgeons.

Electricity came to the town in 1911 with the installation of a privately operated plant and system. Shortly thereafter, a Calumet telephone line was put into service, and it connected with a grid of 12 lines among outlying farms (“party-line” phones) as well as to other regional telephone systems (all independently owned companies before a much later integration of telephone communication).

In 1914, the population of Calumet was around 300.(6)

The Circumstances of the Calumet German Band Photo

Weather data show that the temperature on 4 June 1909, a Friday, was typical for the month: a high of around 80 degrees and a low of 55.(7) But local residents and especially farmers might have appreciated a reprieve from recently heavy precipitation. There had been more than six and a quarter inches of rain in the past two weeks, more than typically falls during the entire month of May.

The setting of the band’s photo is lost to history, the photographer unknown. But a close look shows details that provide insight on the time and the place.

The band is posed within a planted pasture (not native prairie), with brome and other grasses evident in the foreground. At back is a stand of relatively young maple trees. Again, the trees would have been planted; except for a few willow trees that lined a nearby creek, this portion of O’Brien County would not have had native trees when pioneer settlers arrived in the last decades of the 19th century. These trees were likely planted to provide shade for livestock in the pasture. (Maple trees were also a popular choice for planting around homesteads and elsewhere; just three years previously, in 1906, some 1,400 maple and box elder trees had been planted in the new Calumet park mentioned above.)

But the pasture land seen here would change dramatically over the next half century. In the next decades, grazing areas for beef cattle, hogs, sheep, and other livestock would make way for fully tilled fields, as the much greater value of northwest Iowa soil for grain crops would be fully recognized. Dairy operations, which in 1909 would have been primarily for the family’s own use, would almost entirely disappear in the coming decades as intensive grain production became the norm. By the mid-20th century, monoculture agriculture (almost exclusively corn and soybeans) had come to dominate in the region. Likewise, by the late 20th century, livestock that previously would have been common sights roaming on pastures such as the site of the Calumet German Band photo would be generally out of view, housed within large feedlot and confinement operations, and working horses and mules that also would have been seen on pastureland in 1909 gave way to fully mechanized agriculture.

The photo of the Calumet German Band was published in The Des Moines Register on 6 December 1964, 55 years after it was taken, as an interesting historical curiosity for readers. It was republished locally on 7 April 2005 by The Sutherland Courier. In those newspaper renderings, a caption identified band members by name.

Additional Photo from 1912

See a discussion in the “Musical Issues” section about a second photo of the band, dating from 15 October 1912.

The next section, “The Cultural Milieu,” is a companion piece to this one, expanding on this section by discussing issues of ethnicity, culture, language, religion, and farming practices. It also includes brief demographic information about Calumet German Band members.

Footnotes

(1) O’Brien County is named not for an early settler or notable resident. In 1851, when the state legislature split off an additional 49 counties from the territory’s original 44 counties, it decided to honor William Smith O’Brien (1803-1864), an Irish patriot who led the movement for Irish independence at that time.

(2) The name Calumet was probably chosen by the Illinois Central Railroad, which was headquartered in Chicago. Within and around Chicago, along the south shore of Lake Michigan, Calumet is a common place name, assigned by early geographers and planning authorities to the region as a whole (a hydrological subset of the Great Lakes Basin) and to numerous rivers, canals, streets, and towns. The origin of the word is uncertain; it is a colonial-era French term for a type of ceremonial pipe used by some Native American populations, but it may also represent a French transliteration of a Potawatomi word for a low, deep body of water.

(3) Past and Present of O’Brien and Osceola Counties, Iowa, by Hon. J. L. E. Peck and Hon. O. H. Montzheimer (for O’Brien County) and Hon. William J. Miller (for Osceola County). Vol. I. Illustrated. Indianapolis, Indiana: B F. Bowen & Company, Inc., 1914.

(4) In fact, a tiny town called Erie, or Old Erie, a few miles southwest of Calumet, did not survive once the railway connected Calumet, but not Erie, to the outside world.

(5) This centralization was not without controversy. Farmers within the township opposed the building of the central school. At one point an impromptu vote on a tax to fund the school was organized within the town of Calumet, largely in secret, but the issue went down to defeat when farmers caught wind of the plan — causing hard feelings between farmers and town residents. Eventually, however, a bond issue did pass, and a school at the western edge of the town was assembled. Initially this involved moving one of the sub-district schools in 1900, and adding additional cement-block buildings and a brick addition. On 1 March 1925, this assemblage was destroyed by a fire, necessitating school classes to be held in various locations throughout the town until a replacement could be built; the new school opened exactly one year later, on 1 March 1926. The rural sub-district schools did not close immediately, however; some of them continued in operation for a number of years.

(6) This estimated population probably represented a high point. Like many rural areas of Midwestern states, economic forces and the trend toward urbanization would produce a steady decline in small-town population over the coming decades. Some towns that benefited from favorable geography, political importance (e.g., a county seat), or a diversified economic base were able to thrive or be consolidated into larger population areas, but many small towns such as Calumet would shrink or disappear. For example, the nearby towns of Gaza (mentioned above), Germantown to the west of Calumet, and several other small towns in O’Brien County dating from the late 19th or early 20th century are today little more than historic place names. The 2020 census reported the population of Calumet to be 146.

(7) National Centers for Environmental Information, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/cdo-web.